Interviewees Shuji Kurimoto

He is a forestry specialist who has been involved in the cultivation, maintenance, and regeneration of forests for about 50 years. As the representative of the Osaka Prefectural Forestry Association and a certified engineer in the forestry sector with a high level of expertise, he is committed to creating forests that will be passed on to the next generation, preserving both his own and his predecessors’ knowledge and experiences.

For the people of Osaka,

Forests were an essential resource for life

— First, please tell us about the characteristics of Osaka’s forests.

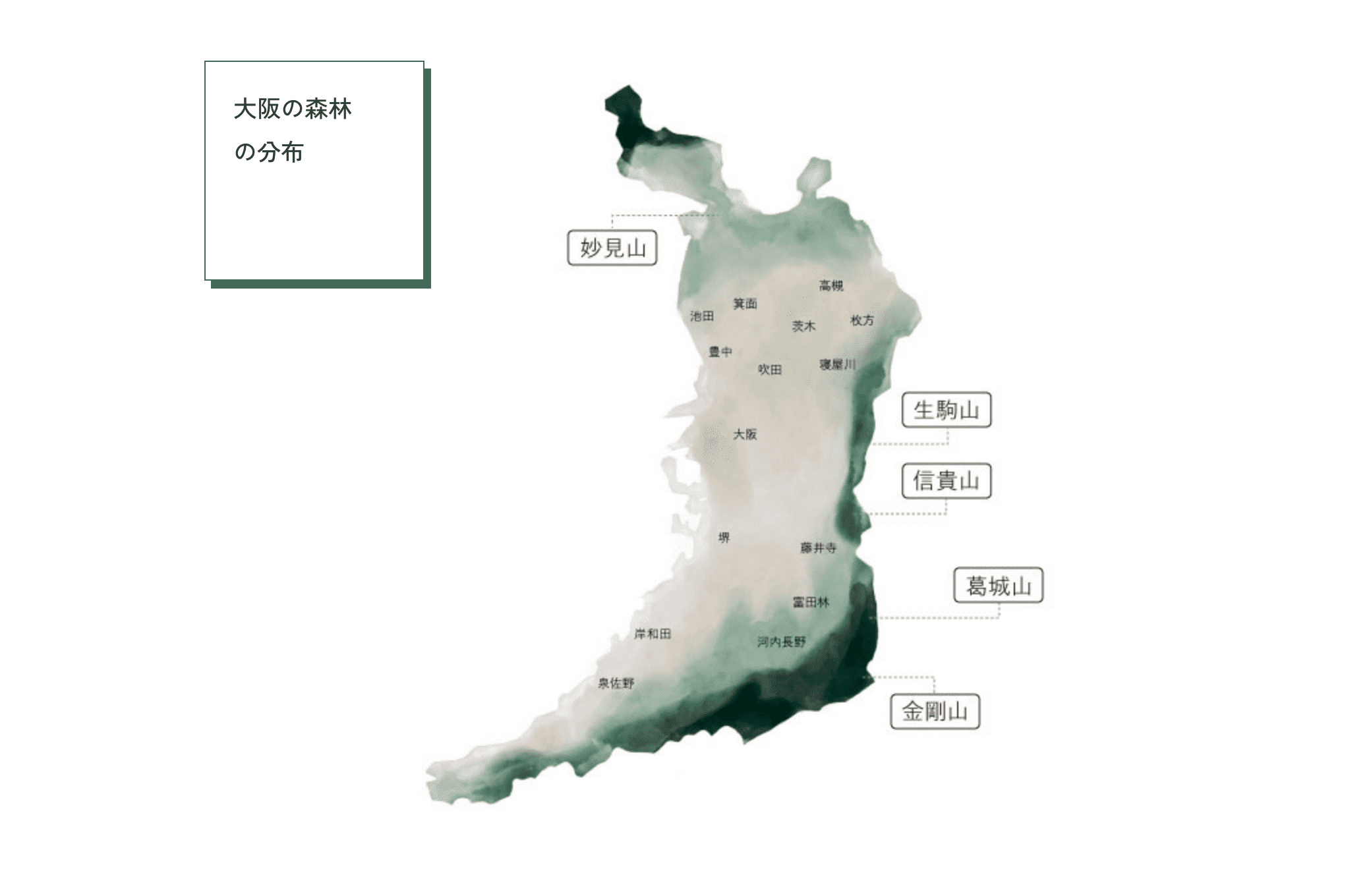

As you may have imagined, Osaka is not an area with many forests. It has the smallest forested area in Japan, approximately 56,000 hectares. Even so, about one-third of the entire prefecture is covered in forests. The Hokusetsu Mountains to the north, the Ikoma Mountains to the east, and the Kongo and Izumi Mountains to the south all extend beyond Osaka’s borders into neighbouring prefectures. In other words, Osaka’s forests (mountains) themselves form the prefectural bound

A major feature of Osaka’s forests, compared to those in other prefectures, is their proximity to urban areas where people live. Since it is convenient to transport forest resources, Osaka’s forests have often been utilised to supply essential goods for daily life, adapting to the needs of the local people.

— How exactly were they utilised?

The production of firewood and charcoal predates the war. Firewood production was conducted close to the city centre, while light and easy-to-transport charcoal production was more common in the hinterlands. Hence, at that time, the Satoyama (village woodlands) was developed with forests centred on Konugi (Sawtooth oak) and Konara (Pin oak), which were well suited for firewood and charcoal production.I have heard that in the past, even in the Takatsuki area, firewood and charcoal were transported to the Yodo River by oxen and then transferred onto boats for delivery to Osaka City.

In addition, the practice of ploughing plants into fields to enrich the soil is called “green manure”. Villagers who did not own mountains paid landowners for the right to use them, allowing them to collect green manure for rice paddies and firewood, which was essential for daily life.

In addition, each region’s forests have their own characteristics.In the southern part near Wakayama Prefecture, Ubame oak (the primary raw material for Binchotan charcoal) was frequently harvested. In areas with pine forests, matsutake mushrooms were collected, and in the north, chestnuts were cultivated. In the hilly areas, Moso bamboo grew, and bamboo shoots were produced.

Trees have disappeared from the mountains!?

Our predecessors put everything into the revival of the forest.

— In the past, were there more forests than there are now?

In fact, the total forested area of the mountains has not changed significantly since ancient times. Historically, Osaka has always had relatively few forests. However, due to the small forested area, mountain resources have been limited. Trees were cut down to produce firewood and charcoal essential for daily life, and during the war, pine root oil was extracted and used as fuel for airplanes, resulting in a significant number of trees being harvested for wartime supplies.In some areas, entire forests disappeared, transforming certain mountains into “bald mountains.” The northern part of Senshu was particularly affected. This area consists of granite, with fragile and easily eroded soil, and from a distance, the exposed white rock surface appeared as if it were covered in snow.

— Did you restore it?

Yes. Restoring a mountain that has lost its soil and where trees can no longer grow is an extremely difficult task. The method called “Sujiko” (which involves building terraces, filling them with soil, and planting saplings) was employed. Not only forestry workers but also additional labourers were mobilised to carry soil to the top of the mountain by hand. To restore greenery, we planted trees such as Japanese Acacia and Yashabushi, which grow well in poor soil, and planted red pine and cypress in areas where even a small amount of soil remained.

Post-war, efforts were made not only to restore the mountains that had become bald but also to rehabilitate forests that had been excessively logged during the war. Those in the forestry business invested their bonuses to plant, nurture, and manage new trees. Thanks to the hard work of our predecessors, the forests in Osaka today remain almost identical in size to those before the war.

The decline of the forestry industry, environmental changes…

Still, the forest has survived because of those who continue to protect it.

— With such changes in the forests and the passage of time, has the relationship with people also changed?

After the war, the cedars and cypresses planted to restore the mountains were initially used as thinned wood for scaffolding in building construction. As they grew to a certain extent, they were then used for housing. During the period of high economic growth, the forestry industry flourished in response to the increasing demand for housing, particularly in the southern Kawachi region and the northern Senshu region. At the same time, as industrialisation progressed, more people left the forestry sector in search of alternative sources of income. Until then, firewood and charcoal production had remained unchanged, and matsutake mushrooms and chestnuts were also harvested. Those who wished to continue working in forestry adapted to the town’s diverse needs by cultivating shiitake mushrooms to sustain their livelihoods, producing charcoal with higher added value, and carefully growing cedar and cypress trees, which were in high demand for housing.

Around the time of the 1970 Osaka Expo (Japan World Exposition), many “Prefectural Forests” were established, particularly around the Ikoma Mountains. These natural parks were developed by Osaka Prefecture to provide green spaces for its residents. Unlike parks created within cities, these forests offer people the opportunity to experience authentic nature in the mountains. This distinctive relationship between people, towns, and forests is unique to Osaka, where urban and natural environments coexist in close proximity.

— As the number of wooden houses decreases due to modernisation, will the composition of forests also change?

It is true that domestic timber has long been rarely used for interior materials and prefabricated houses. However, some places in Osaka still employ traditional construction methods, using domestic wood for pillars. Moreover, trees grown in Osaka on poor soil tend to have narrow and uniform growth rings. When cultivated with care—such as through branch pruning to remove knots—these trees produce exceptionally high-quality timber, which is currently traded at a higher price than that from other regions.

However, if a tree is subjected to a typhoon—even if it does not fall—the violent shaking can cause internal fibres to break, leading to a decline in its quality as timber. In recent years, typhoons have become more frequent due to climate change and other environmental factors. Moving forward, it will be necessary to create disaster-resilient forests by incorporating broad-leaved trees between cedar and cypress plantations to act as buffers.

It always has been, and always will be.

In the spirit of “continuous culture”.

— The forests that we have long taken for granted are being preserved through great effort and ingenuity.

People involved in forests have a strong sense of “forests within the community.” Therefore, in addition to cultivating forests in ways centred on being useful to locals, they also ensure safety by cutting down dangerous trees in preparation for disasters and managing water and air quality to prevent environmental damage. In this sense, forestry is also deeply connected to agriculture. In a society that values agriculture, forests are properly maintained and managed, which in turn preserves the environment. As long as this awareness remains, Osaka’s forests will continue to be protected.

We often hear the word “sustainability” these days. In the forestry industry, the concept of “continuous culture” has long been stipulated by law. In other words, “Recognise the need to preserve and nurture.” This is what we now refer to as “sustainability.” It is the very spirit of forestry that has been deeply rooted in our ancestors.

— What kind of future development do you envision for the forest?

As I have mentioned so far, Osaka’s forests are characterised by their proximity to the city, and they have survived by incorporating greenery and supplying the necessities of life to meet people’s needs. Regardless of how many industrial products exist, the warmth and texture that can only be found in natural wood remain unchanged. Having greenery nearby attracts birds into the city, and without us even realising it, forests bring colour and vibrancy to our lives. I hope that by continuing to closely interact with people, the forest will continue to thrive and evolve.

Currently, specific initiatives are being implemented in some areas, with efforts underway to create forests where young people can volunteer, enjoy a picnic while eating their packed lunches, and children can have fun catching insects. Moving forward, we look forward to fostering connections between urban residents and forests through these new ways of engaging with nature.